By Hannah Jones

On a Friday back in February, Kirsten and I attended the Detention Forum annual social event, which was in the form of a discussion ‘salon’, focusing on the question “what is immigration enforcement doing to us?”. There was a great turnout for an event confronting such a grim issue on a Friday evening. Many of those in attendance had also spent the day discussing immigration detention too, as part of the Forum’s campaign for a limit on the amount of time that people can be kept in immigration detention (the UK is the only European country where this can be indefinite).

Detention Forum Salon February 2015. L-R Ben du Preez, Aderonke Apata, Hannah Jones, Kirsten Forkert, Harley Miller, Ian Dunt, Eiri Ohtani. Photo courtesy of The Detention Forum.

We had been asked to share some of our findings as a way of kicking off the panel discussion. It was a lively discussion, and while there wasn’t much chance for the audience to engage with the debate in the room, several people there did make comments through Twitter (see #DFSalon for a taste of this). One comment in the discussion which seemed to resonate very strongly was the need to confront how immigration enforcement is no longer just about passport checks at the border, or even just uniformed officers patrolling the streets. Landlord checks being piloted in the West Midlands mean all private landlords are charged with verifying the immigration status of any prospective tenant, under threat of fines, and it seems many are already making decisions based on guesswork. NHS staff are being asked to request proof of immigration status from patients, when they could be spending time on healthcare. Universities – and ‘even’ prestigious private schools – are being required to report to the Home Office on the attendance of overseas students, with some setting up ‘immigration offices’ within the university and many going over and above the legal requirements, in fear of having their ability to host lucrative international students taken away. While university staff may try to avoid this – and to try avoid breaking the law on discrimination – by abiding by their union’s guidance and applying any such checks to all students, the consequences of missing a ‘monitoring point’ cannot be the same for UK and EU students as they may be for non-EU students, who risk being deported. Some of these instances of everyday passport control may be shocking, but also note that it has become unremarkable that employers now ask for a passport before issuing a contract of employment. In the case of employment, this is asked of everyone; in many of these other cases, it is likely that only those who ‘seem like’ they may not have citizenship or entitlement will be asked to prove they belong.

This takes us back to another key point raised at the Salon. Journalist Ian Dunt, who was also on the panel, made a strong argument for the need for news and comment stories to be ‘relatable’, that is, in order to care about an issue, or even read to the end of an article, readers should be able to see that it could happen to them or someone close to them. The example was given of another panellist at the event, Harley Miller. As she outlined in her presentation to the Salon, her encounter with Home Office Immigration Enforcement happened suddenly and was shocking to her, those around her, and the many people who picked up and followed her story as it went viral online. As an Australian previously married to an EU citizen, who had lived in the UK for many years on a perfectly legal visa and working in a highly skilled profession for the NHS, her life was turned upside down when the Home Office refused to renew her visa and her status in the UK – her home – became ‘illegal’. For Dunt, this story is one that ‘ordinary people’ can relate to, because they can identify with Harley and imagine themselves in her position, much as the campaign group BritCits has taken off as the clampdown on immigration rules increasingly affect all British citizens who might want to marry someone from outside the EU.

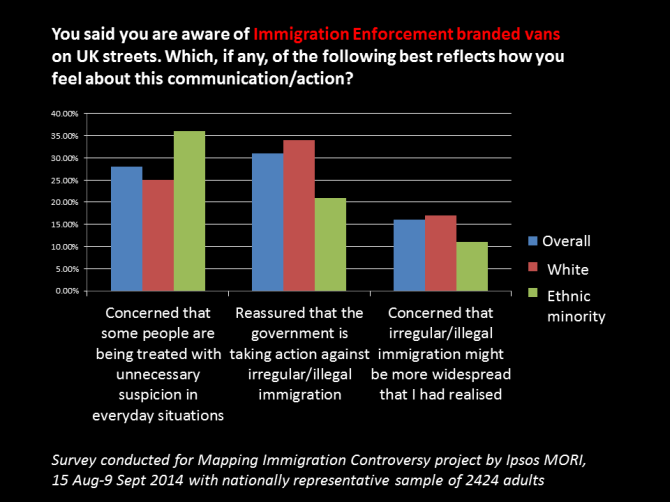

This raises interesting questions when we look at some of the results of our national survey[1] on reactions to immigration enforcement measures among the general population. When we asked people who were aware of Immigration Enforcement branded vans on UK streets how they felt about seeing these vans, 31% of people said they felt reassured that the government was taking action against illegal or irregular immigration. 28% said it made them concerned that some people are being treated with unnecessary suspicion. And 16% said it made them think that illegal or irregular immigration might be more widespread than they had realised. This suggests that, like many of the measures the government is using to demonstrate ‘toughness’, these vans barely reassure more people than they worry – and they actually increase worry among a significant number of people who see them.

But then look at the breakdown between the reactions of white majority respondents, and ethnic minority respondents, to that question. More ‘white’ respondents (34%) were reassured than for the population as a whole. And far fewer ethnic minority respondents (21%) were reassured by these vans. This was reversed for those who were concerned that the vans may indicate that some people were being treated with unnecessary suspicion – only 25% of white respondents thought this, but 36% of ethnic minority respondents. That is, ethnic minority respondents were much more likely to see the enforcement vans as a stunt, but also as a stunt that could result in unfair treatment. Ethnic minority respondents were also much more likely to be aware of these vans (23%) than white respondents (16%).

This suggests that there may well be a connection between being able to see oneself in a situation, and how one reacts to it. That ethnic minority respondents were so much more likely than white people to worry about people being treated with unfair suspicion as a result of more high visibility immigration enforcement raids may well have something to do with their experience of being unfairly treated with suspicion in similar situations. As one of our focus group respondents told us,

“people can’t tell who is legal or illegal and they make judgements based on your appearance, sometimes that changes when they hear your accent”

So what do people mean when they say ‘ordinary people’? Aderonke Apata, who also talked about her experience at the Detention Forum Salon, is an ‘ordinary person’ too. Actually, she’s extraordinary in many ways – her survival and her campaigning, and her recognition as a role model attest to that. But she is also ordinary in that her main demand is ‘I want to be who I am’. In order to survive, she had to flee the country she lived in, survive the murders of many people close to her, endure immigration detention in the UK where she also experienced homophobic harassment, and sleep on the streets to avoid deportation to a country where she would be punished for her homosexuality with up to 14 years in prison. She is continuing to appeal her asylum case after the most recent ruling on her case by a High Court Judge on the basis that he did not believe she is a lesbian, despite her providing evidence of her relationships with women. It might be hard for many people in the UK to imagine that series of events happening to them. But maybe they could imagine themselves or someone they know being persecuted for their sexuality. And maybe it doesn’t take such a great leap to see the connections between that, and Aderonke’s experience.

Ian Dunt argued that the politicians, journalists and decision makers still tend to be middle class white men who will identify more with ‘people like them’ (as London Mayor Boris Johnson’s statements on UK-Australian immigration seem to attest). But there is nothing particularly ‘ordinary’ about politicians, journalists and decision makers. Isn’t it time that campaigners, commentators and others recognise that ‘ordinary people’ are not made in the image of the London elite, but have lives and experiences that are complex, diverse, and that can allow for identification with and care for people in all sorts of situations – including immigration detention?

And time too for journalists, campaigners, and even social researchers to start to recognise that many ‘ordinary people’ have been on the sharp end of immigration enforcement for a long while?

Ordinary people are not just subject to immigration enforcement, they are also increasingly being required to enact it. What is this doing to all of ‘us’?

[1] All statistical data in this article is based on a face-to-face survey conducted for Mapping Immigration Controversy project by Ipsos MORI, 15 Aug-9 Sept 2014, with nationally representative sample of 2424 adults.

Pingback: Windrush and Go Home: the whittling away of both rights and responsibility | Mapping Immigration Controversy